The decision-making frameworks that help companies like Amazon, Pinterest, and Shopify get more growth

In the early days of building a product, you’re often just a small team sitting around a room. It’s easy to move quickly — all it takes to get started is turning to the person next to you.

If you’re not careful, development grinds to a halt. Figuring out how to scale decision-making from a small group to a larger company with multiple teams becomes a matter of survival.

The trick is to get aligned on a high-level and devise a method for how decisions are made. That allows your team to spend less time debating what to do, and more time actually doing it. In this article, we’ll examine the decision-making frameworks that allow massive companies like Amazon, Google, and Facebook to make better decisions faster.

Disagree and Commit at Amazon

Amazon is a company famous for data-driven decision making, launching hundreds of simultaneous A/B tests on their website at once on everything from the placement of the buy button to Amazon Prime membership prices.

At the heart of this is Jeff Bezos, the company’s founding father. Jeff advises team members at Amazon:

Use the phrase “disagree and commit.” This phrase will save a lot of time. If you have conviction on a particular direction even though there’s no consensus, it’s helpful to say, “Look, I know we disagree on this but will you gamble with me on it? Disagree and commit?” By the time you’re at this point, no one can know the answer for sure, and you’ll probably get a quick yes.

This is an approach that has served Bezos well at Amazon, which recently crossed a foundation of $575.16B. After years of keeping margins low and the company unprofitable, Amazon this year has roared to life.

The secret behind this principle is that there are two types of decisions that companies face. Some decisions are not reversible, which means that they require more cognitive effort and caution. Other decisions are easier and simpler to experiment with.

The “disagree and commit” principle works, as Bezos points out, because most decisions are actually this second kind. They’re reversible — which means that if you’ve created a culture of experimentation and course-correcting, being wrong is often less costly than you expect. On the flip side, being slow means missing out on more opportunities with huge potential upside.

Commit to Action

In the early days of Amazon, an engineer named Greg Linden had an idea to send users recommendations based on the items that were already in their shopping cart. Linden believed that recommendations would increase the amount that customers purchased.

The only problem? A senior vice-president disagreed.

The SVP argued that a recommendations feature might distract customers from checking out, and discouraged Linden from working on it. Instead, Greg ran a live test online around his recommendations idea. Not only did the results support Linden’s idea, but it showed that not having shopping cart recommendations was hurting Amazon’s bottom line. The team committed to the winning idea full-throttle.

While team members may have disagreed about what the outcome of an experiment would be, committing to running the experiment meant they didn’t have to spend more time arguing about it. They were committed to a method, rather than pre-determined biases.

As Linden says,

Everyone must be able to experiment, learn, and iterate. Position, obedience, and tradition should hold no power. For innovation to flourish, measurement must rule.

Scaling Experimentation at Pinterest from the Bottom-Up

When Pinterest began, the company was unpalatable to venture capitalists. To get an initial audience, Pinterest founder Ben Silberman went to the Apple store in Palo Alto and set the home pages of all the computers to Pinterest. Rather than targeting a crowd of millennial early-adopters, Pinterest’s early audience was populated by stay-at-home moms in the Midwest.

With a $12B valuation and 150 million monthly active users, Pinterest today is proving the naysayers wrong.

Casey Winters, a former growth lead at the company, played an instrumental role in taking the company to where it is today.His advice for achieving rapid growth? Go after the big problems first.

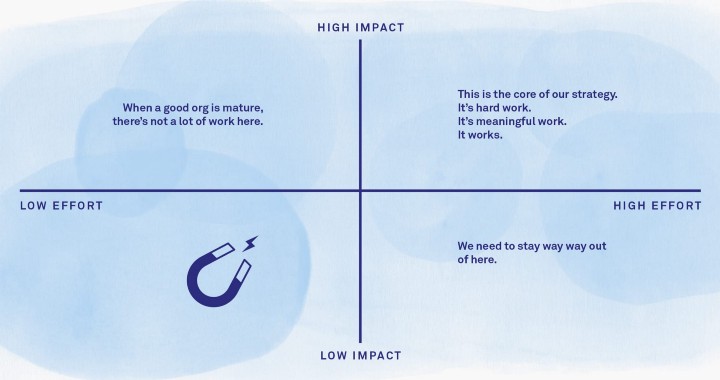

That does not mean tackling the hardest problems first. Instead Winters recommends that you “find an easy problem to solve that has a high impact for the business, and hopefully a very high iteration cycle, because growth needs to run a lot of experiments to learn.”

To drive greater experimentation and growth at Pinterest, it was crucial that the growth team could come back to the rest of the company with real, tangible, results that demonstrated immediate value.

Low-Effort, High-Impact Growth Wins

Winters and his team began by finding problems where they could achieve maximum impact with the least amount of effort before tackling the harder, thornier problems.

Here are a couple ways that Pinterest prioritized early growth wins:

- Sign-ups: One of Pinterest’s most successful, early experiments was a simple banner that popped up as a visitor was scrolling down a Pinterest feed with a “sign up to see more” call-to-action. This test increased conversions by 50%.

- Mobile App Installs: As Pinterest was encouraging more user growth, they noticed that people who used the mobile app were up to 4 times more engaged than mobile users. To encourage greater mobile app use, they experimented with their activation funnel to juice engagement. One Pinterest engineer ran 15 different iterations on the mobile website to nudge them into the app.

- Onboarding: Conventional wisdom around user onboarding says that you should onboard users by teaching them how to use the application. Early on, Pinterest designed a carefully constructed email onboarding flow that did exactly that. To their surprise, they found that these instructional emails were actually skyrocketing unsubscribes. What worked were emails that sent people relevant content on Pinterest.

While some of these experiments seem obvious, the ability to rapidly decide which growth decisions to optimize and see immediate and impactful results allowed the team to gain momentum. Then, they could tackle the bigger, thornier problems.

Shopify’s Compass Metric

Shopify, the e-commerce platform, began 13 years ago as an online store for selling snowboards called Snowdevil. Shopify founder Tobias Lutke had built the backend for Snowdevil from scratch. As interest in selling online was swelling, Lütkequickly realized that there was a much bigger opportunity for selling a hosted e-commerce service than there was for snowboards. That was the start of Shopify.

Today, Shopify is a public company that does everything from providing merchants with a full set of ecommerce tools, to helping them sell in brick-and-mortar stores, to a conversing with customers via Facebook Messenger.

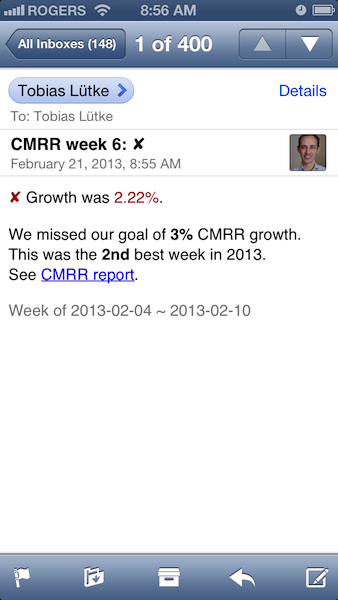

Lütke points out that to get to achieve this growth, one of the most important things for Shopify was figuring out what single metric to focus on — their so-called “compass metric.” By picking a compass metric:

You implicitly tell your team that if someone moves this metric in the right direction they are doing a good job. If you launch a lot of experiments you can sometimes allow people to use other metrics for some early readings, but you should only conclude the efficacy of your experiments by checking the impact on your compass metric.”

Your compass metric might be relatively straightforward, like monthly recurring revenue or daily active users. Or it might be something specific to your product, such as friends added in Facebook or items pinned in Pinterest. The important thing is that it aligns your team around one single goal. That way, they can spend less time figuring out what to do, and more time doing it.

Weekly Meetings

To make progress in increasing CMRR, Shopify did one simple thing. They ran a weekly meeting attended by everyone who had an impact on their compass metric, from sales reps to marketers. At the meeting, each team member would talk about two things:

- What they learned that week

- What they were planning on doing differently next week

This helped Shopify create a high level of both accountability and autonomy around lifting their compass metric. Team members were empowered to make their own decisions, but held accountable for learning from those decisions and improving. This helped the team launch a high volume of experiments, track how well those experiments were performing, and iterate on what they’d learned each week.

As Lütke says, “this is the motor of a fast-growing multi-million dollar venture-backed business.”

High-Velocity Decision Making

There’s no one-size fits all solution to making decisions, and the way that you approach it will invariably shift. What works for Amazon, Pinterest, or Shopify might not make sense for your team — and that’s fine. Within the context of your business, the goal is to eliminate friction and enable team members to make decisions and learn, faster.